How to Publish a Book on Amazon and Make Money: A Beginner’s Guide

September 24, 2025

What Is an ISBN Number? 7 Steps on How to Get Your Book’s ISBN

September 25, 2025If you’ve ever wondered how to book spine design works or why it’s so important, you’re not alone. Authors often focus on the front cover and forget the spine, but on a crowded shelf, usually only the spine is visible to readers. A well-designed spine can intrigue a browser and convey crucial information at a glance. In this comprehensive guide, we’ll explain everything about book spines from what they are and how to design them, to even how to fix a book spine if it gets damaged. Our goal is to inform, entertain, and educate you on this technical aspect of your book’s cover, so you can make your novel stand out and see why working with a quality publishing partner (present or future) is worth it.

“… The facet of physical books that endow book-buying with its romance and mystery, that truly distinguishes one book from another, is … the spine.” — Kari Larsen

What Is the Book Spine (and Why Does It Matter)?

The book spine is the narrow edge of your book where all the pages are bound together, essentially the book’s backbone. It connects the front and back cover and gives the book structural integrity. Beyond its physical role, the spine is also a vital piece of real estate for information and branding. In a bookstore or library, the spine is often the only part of the book a person sees on the shelf. That makes it a critical marketing tool: a good spine design catches a reader’s eye, conveys the title and author clearly, and invites them to pick the book up. In short, an eye-catching spine can make the difference between someone noticing your book or passing it by. Don’t underestimate its importance!

Key Elements of Book Spine Design

Knowing what to include (and what not to include) on your spine is the first step in learning how to design it effectively. The book spine should display the most important information at a glance: typically the book title and author’s name, plus a publisher’s logo or imprint symbol if applicable. These elements are usually arranged in a simple hierarchy:

- Title: The title is generally placed toward the center or top of the spine and should be the most prominent text. It’s often set in a clear, bold font so that it’s readable from a distance.

- Author Name: The author’s last name (and sometimes first name, if space allows) is also included, usually towards the middle or bottom. New authors especially benefit from having their name visible to build recognition. However, avoid long credentials or subtitles on the spine, too many words will clutter the small space.

- Publisher Logo: It’s common to put a small publisher’s logo or imprint at the very bottom of the spine. This adds a touch of professionalism and branding. If you’re self-publishing, you might use your own imprint logo or simply omit this. It’s an optional element, but one that can lend credibility.

Keep the spine text minimal and focused, typically, subtitles or taglines are left off, unless you have a thicker spine with room for a short subtitle. Remember that clarity trumps completeness on a spine. A few well-chosen words (title/author) have far more impact than squeezing in every detail.

Make It Readable: Orientation & Typography

The orientation of the text on your book spine is important for readability. In English-language markets like the U.S. and U.K., the convention is to have the text run from top-to-bottom along the spine (so when the book stands upright, you read the spine text by tilting your head to the right). In some European countries, the opposite orientation (bottom-to-top) is used, but today most publishers stick with the top-to-bottom format for consistency. It’s best to follow the standard of your market so that your book looks “normal” on the shelf.

Choose a font that is clear and legible at a small size. Fancy script or overly decorative fonts might look nice on a full cover, but on a skinny spine they can be hard to decipher. Opt for clean, high-contrast typography. Bold sans-serif or serif fonts with good weight tend to work well because they remain readable even when the spine is only a few millimeters wide. Make sure the text color stands out against the spine background color, for example, light text on a dark spine or vice versa, so that the title and author don’t blend into the background. Your goal is for a reader to spot your title instantly among dozens of books.

Also, center your spine text. Centering the title and author name on the spine (both vertically and horizontally in that narrow space) creates a balanced, professional look. And always leave a small safety margin, at least about 1/8 of an inch of blank space on either side of your spine text, so nothing sneaks onto the front or back cover during printing. Printers can have slight shifts in alignment, so you don’t want any text too close to the edges of the spine.

- Keep it simple: Don’t overload the spine with information or complex art. Clean design and a bit of strategic whitespace will help your title pop.

- Go bold: Use bold, easy-to-read fonts for the spine text so that it jumps out at browsers even from a distance. This is not the place for delicate or very small type.

- Add a graphic (if space allows): If your spine is wide enough, a small graphic element or icon can draw the eye. This could be an emblem from the cover, a series logo, or any image that relates to your book. Just ensure it doesn’t interfere with legibility of the title.

For example, children’s books often include a tiny illustration or fun icon on the spine to entice young readers (and to look attractive when the books are lined up). If you have a series, you might use a consistent symbol or number on each book’s spine to help readers identify the sequence. Use these embellishments judiciously, they should complement the title/author text, not compete with it.

Color and Graphics: Stand Out but Stay Cohesive

The spine’s color scheme should both catch attention and match your overall cover design. Some designers treat the spine as an extension of the front cover artwork, for instance, wrapping the cover image or background color onto the spine and then onto the back cover, creating one continuous design. Others prefer to use the spine as a contrasting stripe that separates the front and back covers (for example, a solid color spine that differs from the cover art). Either approach can work, so long as the spine’s color helps the title stand out. Avoid very busy patterns or images on the spine if they make the title hard to read. Often, a plain or solid-color spine with high-contrast text is the safest bet for visibility.

Make sure to maintain consistency with your cover: use complementary colors and the same or similar fonts as the front cover so the spine doesn’t feel like a random afterthought. Many successful book spines pull a key color from the cover or use a simplified portion of the cover image, so the whole book has a unified look. This also creates a nice effect when several books in a series are placed together, they will have a matching style. Speaking of series, if you’re designing a series of books, plan the spines together. You might, for example, align all the titles and volume numbers in the same position and use a consistent font, so that when the series sits on a shelf, it looks neat and coordinated.

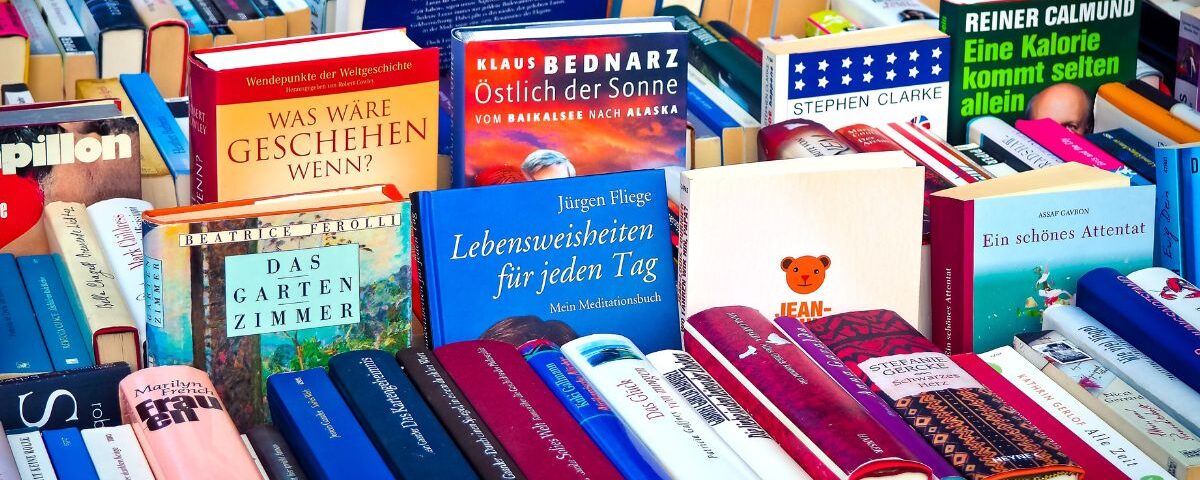

Below is an example of some book spines that got it right. Notice how these spines use clear, bold titles and carry over design elements or colors from the front cover, creating a distinctive look for each book while remaining highly legible:

Several examples of well-designed book spines. Each one uses readable fonts and strong contrast, and often borrows colors or graphics from the cover to give the spine a unique flair.

As you can see, an effective spine design balances creativity with clarity. A splash of color, a unique font treatment, or a small graphic can provide the “wow factor” to make your book spine pop off the shelf, but the core information (title/author) must still be instantly clear. Always step back and ask yourself: from a few feet away, will someone be able to read my spine and get a feel for the book’s style? If yes, you’re on the right track.

Calculating Spine Width and Layout

Designing a book spine isn’t just about aesthetics, there’s a technical side to it as well. One of the first technical considerations is determining how wide the spine needs to be for your particular book. The spine width depends on two main factors: the number of pages in your book and the thickness of the paper used. In printing, paper thickness is often measured as PPI (pages per inch), indicating how many pages equal one inch of thickness. For example, a common paperback paper might be around 400 PPI, meaning 400 pages = 1 inch spine.

You can calculate an approximate spine width with a simple formula: Spine Width = page count / PPI. So if you have a 350-page book printed on 400 PPI paper, the spine would be 350/400 = 0.875 inches wide. (If that same book were on thicker paper, say 250 PPI, the spine would be 350/250 = 1.4 inches, and on thinner 500 PPI paper it would be 0.7 inches, and so on.) In the case of hardcover books, remember to add the thickness of the cover boards. Hardcovers have two boards (front and back); each may be around 0.125 inches thick, so adding about 0.25 inches extra to the spine width for a hardcover is typical.

Most self-publishing platforms and printers will provide a cover template or calculator when you input your book’s specifications. For example, Amazon KDP will generate a PDF template for your cover (including the spine) once you enter your trim size and page count. It’s wise to use these templates, they show the exact spine width and also indicate safe zones and bleed areas. If your printer doesn’t provide a template, you can ask them for the precise spine measurement or use an online spine width calculator (by plugging in page count and paper type). In any case, always double-check this measurement before finalizing your cover design.

Keep in mind that very thin books might not be able to fit any spine text at all. Print-on-demand services typically require a minimum page count (for instance, KDP requires ~79–80 pages) to even print text on the spine. An 80-page book has a tiny spine (around 0.2 inches or less), which makes adding legible text extremely challenging. Many experts suggest that about 100 pages (roughly 0.25 inches thick) should be the minimum for attempting spine text. If your book is very slim, say a 40- or 50-page booklet, it’s usually best to leave the spine blank or perhaps just add a small logo, rather than squishing unreadable text on there. There’s no shame in a blank spine for a thin book; it will look cleaner and more professional than microscopic text.

Another thing to consider is the variability in the printing and binding process. When the book is bound, the spine text can shift slightly to either side by a millimeter or two. Furthermore, when pages are trimmed, the cut might not be perfectly centered on your file’s spine every single time. This is why, as mentioned earlier, you should have a healthy margin around your spine text and not have any critical design element ending exactly at the spine edge. In fact, a pro tip is to extend your spine’s background color or design slightly onto the front and back cover. For instance, if your spine is a distinct color, you can bleed that color out onto each cover by about 1/4–1/2 inch. That way, if there’s a slight misalignment when trimming, no white sliver will show and the spine color will still look continuous. Lulu’s print-on-demand guide suggests doing this especially if you have a high-contrast spine color, to avoid it creeping onto the cover visibly if things shift.

Design your cover as one unified file (front cover + spine + back cover together) rather than trying to create the spine separately. This ensures that you account for the spine thickness in the overall layout and that the design flows nicely from front to spine to back. In a cover design software or template, you’ll typically position your spine area in the middle, between the front and back cover areas. The template will mark out the spine region. For example, see the standard cover template below — the center strip (purple in the image) represents where the spine goes, and its width is calculated based on the page count:

A cover template for a paperback (6×9 inch trim). The center bar is the spine area, which must be precisely sized to the book’s page count. Note that the spine width here is just an example, your spine will vary with page count.

When laying out your spine text and graphics, double-check that nothing critical (like your title) strays out of the spine area in your design file. Also, keep all spine content within the “safe” zone as indicated by your template (usually slightly inset from the exact spine edges). This precaution is to prevent any of your text from wrapping onto the front or back cover due to printing variance. Printers typically recommend at least 0.125 inches of safety margin on each side of the spine for this reason.

One more tip: once you have your cover and spine designed, it’s a good idea to print it out on paper (even at home in rough quality) and wrap it around a book or stack of paper with the same thickness as your book. This “mock-up” lets you see if the spine text is centered and sized correctly, and gives you a feel for how it will look on an actual book. It’s an easy way to spot any issues before you send the design to print.

Ensuring the technical accuracy of your spine layout is part of producing a quality book. (It’s also something a professional service can help with, for instance, our team at AGPS Books makes sure your spine dimensions and layout are spot-on as part of our print formatting services.) Take the time to get it right, and you’ll avoid unpleasant surprises like off-center titles or wrap-around printing errors on the finished product.

How to Fix a Book Spine (Repairing a Broken Spine)

Books are meant to be read and loved, which sometimes means they get a bit worn out. If you have a book whose spine has cracked or the binding has come loose, don’t despair! You can often repair a broken book spine yourself with some basic supplies and a little patience. Below we’ll go over the steps to fix a book spine and get your book back in shape.

- Assess the damage: First, figure out what kind of spine damage you’re dealing with. Is the cover’s spine (the outer covering) torn or coming detached? Are the pages (book block) coming loose from the binding? A “broken spine” can range from a small crack in the hinge to the entire cover separating. Identifying the issue will help you choose the right repair approach.

- Gather proper supplies (and avoid regular glue): You’ll need some specialty materials to do a lasting repair. At minimum, get archival book glue (also known as bookbinding glue or acid-free PVA glue) and book repair tape (a special sturdy tape or cloth specifically for binding repairs). Do not use regular hot glue, school glue, duct tape or household adhesives, these can damage the book further over time. Bookbinding glue remains flexible when dry (so the book can open and close properly) and is pH-neutral, which prevents the paper from degrading. Book repair tape is designed to be strong but gentle on paper. You may also want a bone folder (a flat tool for pressing paper), scissors or a craft knife, and a clamp or heavy books to apply pressure while drying.

- Reattach any loose pages or cover: If the pages (or cover) have separated from the spine, your first step is gluing them back in. Apply a thin layer of your bookbinding glue along the inner spine of the cover or the edge of the book block (where the pages’ folds meet the spine). Gently set the pages back into the spine, aligning everything carefully, or press the cover back onto the glued spine area. Make sure everything is straight and the pages are in the correct order. Close the book and use rubber bands or clamps to hold it tightly together while the glue dries. Typically, you should let it dry for at least 8–12 hours (overnight is good) so the glue cures completely. Wipe away any excess glue that squeezes out, before it dries on your pages.

- Reinforce the spine with tape: Once the glue has fully dried and the pages are secure, it’s time to strengthen the outside of the spine. Cut a piece of book repair tape or binding cloth that’s a bit longer than the length of the spine. Center it over the spine and wrap it, sticking it onto the book’s front and back covers adjacent to the spine. This tape essentially acts like a new outer spine, holding the covers and pages together securely. Smooth it down with a bone folder or the back of a spoon so there are no air bubbles. The tape should extend onto the covers by about half an inch or more on each side, for a good bond. This step will fix any external cracks and provide a flexible, sturdy support for the repaired spine.

- Fix minor internal issues: If your spine wasn’t completely broken but you have some loose or “tipping” pages (where the page is starting to detach at the inner binding), you can fix those with a bit of glue as well. Apply a thin line of archival glue along the inner edge of a loose page and press it back into place at the spine, then let it dry under pressure. For small cracks in the inner paper hinges (the joints where the endpapers meet the spine), you can use a narrow strip of tape or glue a piece of thin paper (like rice paper) to bridge the crack. The idea is to shore up any weak spots so they don’t worsen with use.

After these steps, your book’s spine should be much more stable. Always let all glue completely dry before opening the book again, to avoid undoing your work. The repaired spine might not look perfect, but it will function, the book will hold together for many more reads. To keep it in good shape, handle the book with some care (don’t force it flat, for example, if it’s a tight binding).

Preventative care: If you know a book will get heavy use (for instance, a textbook or a beloved children’s book), you can reinforce the spine proactively. Some librarians use clear label protectors or cloth library tape on new books to strengthen the spine from day one. Also, avoid storing books with the spines facing upward (which can stress the binding). Treat your books well, and their spines will thank you!

For more detailed guidance on repairing bindings, you can also consult resources like Book Riot’s guide to fixing broken book spines, which offers a helpful DIY approach. And of course, for extremely valuable or antique books, it’s wise to seek a professional book conservator to do the repairs.

Bringing Your Book Spine to Life: Final Tips

By now, you should have a solid understanding of how to design a book spine that is both attractive and functional. To summarize the key points: keep your spine text bold and readable, use a design that complements your front cover (while still standing out on its own), and double-check all the technical details like spine width and text placement. A great spine design will make your book immediately recognizable and enticing on a shelf.

Don’t worry if all this seems like a lot, mastering book spine design is a skill that grows with experience. The good news is you don’t have to do it all by yourself. Working with professionals or an experienced editorial design team can take the guesswork out of the process. For example, our custom book cover design services include meticulous spine design (ensuring your spine text is perfectly centered, fits the calculated width, and matches your cover’s aesthetics). We’ve helped many authors create covers where the spine not only holds the book together physically, but also becomes a mini billboard for their story.

In the end, a book’s spine might be a slender thing, but it has a big job. It protects your story, projects professionalism, and invites readers in. With the tips and techniques from this A-to-Z guide, you’re now equipped to make your book’s spine the best it can be, whether you’re tweaking the design for maximum impact or repairing a well-loved volume so it can be enjoyed again. Pay attention to this small but significant detail, and you’ll be positioning yourself (and your book) for success. Happy spine designing, and happy publishing!

For further inspiration on creative spine designs, you might enjoy reading how top publishers approach it, see the insights from Penguin Random House designers on what makes the perfect book spine. They emphasize having a single “wow factor,” whether it’s a striking color or a bold typographic treatment. It’s clear that a thoughtful spine can truly set your book apart.